In the Cypriot capital of Nicosia—one of the world’s few remaining divided capital cities—former resident and Turkish Cypriot Yaren Fadiloglulari returns home after nine years abroad, to live on ‘the other side’ that’s majority Greek Cypriots. Here, she reflects on identity, history, and what it’s like being a tourist in your hometown.

Note: This article is not a political analysis; it is a personal essay from someone who grew up in Nicosia and has lived in different parts of the city. The terms ‘northern’ and ‘southern’ refer to directions across the buffer zone.

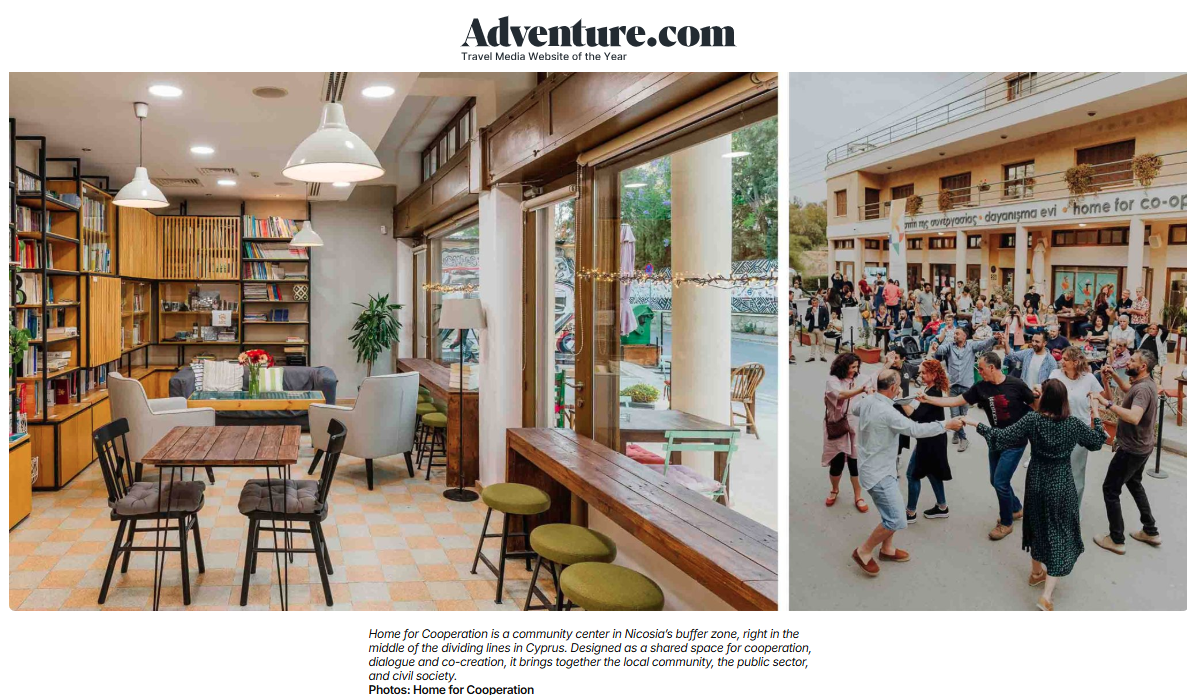

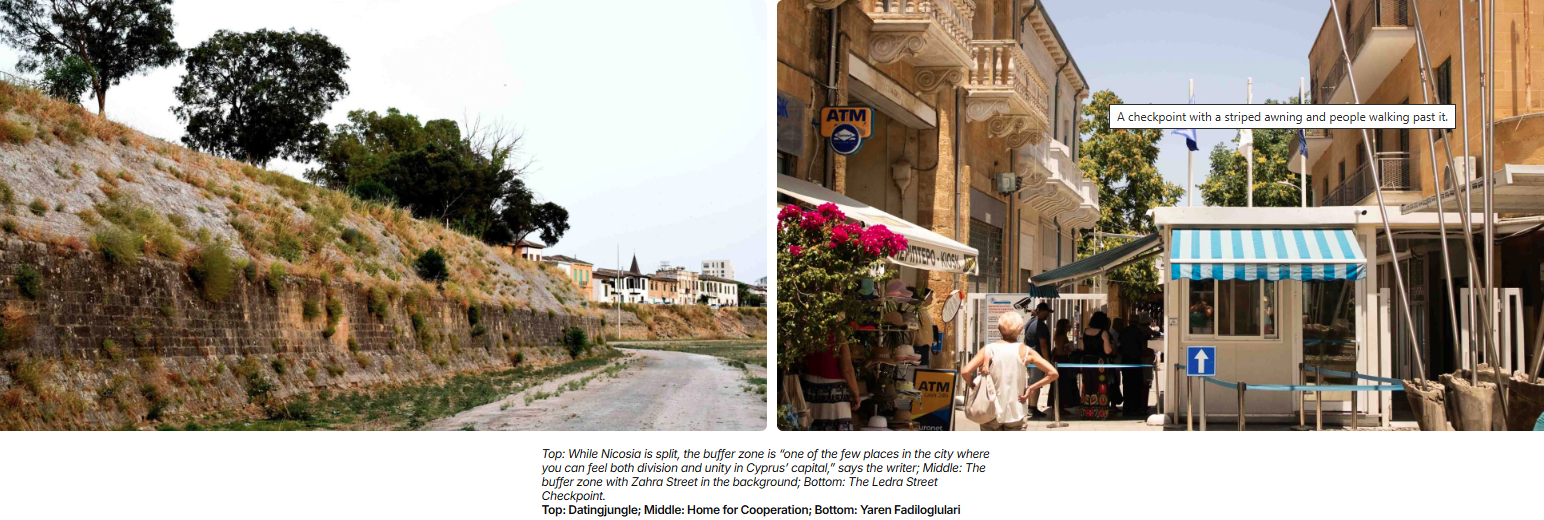

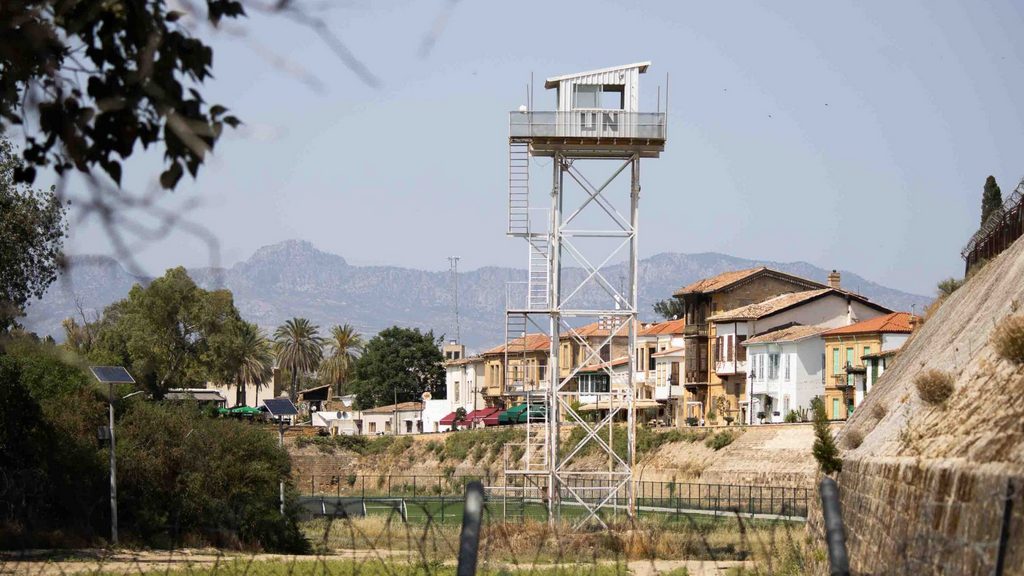

I’m sipping a coffee at Home for Cooperation, a community center in Nicosia’s buffer zone in the Ledra Palace area. All around me people are chatting away in Greek, English, Turkish (or all three at the same time) while outside we’re surrounded by barbed wire and UN peacekeepers. It’s one of the few places in the city where you can feel both division and unity in Cyprus’ capital.

While the physical division is obvious, it feels more united here than anywhere else in the city. There’s talk of peacebuilding projects, bi-communal events between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, and, of course, the ‘Cyprus problem’. In Cyprus, any topic, no matter how big or small, important or unimportant, can circle back to the ‘Cyprus problem’, the longstanding issue between Greek and Turkish Cypriots over the island.

Since 1974, there’s been a UN-operated buffer zone stretching 112 miles (180 kilometers) across the island in the Mediterranean Sea. But Nicosia was divided 10 years earlier (from the end of 1963 through 1964) due to intercommunal conflict. Today, most Turkish Cypriots live on the northern side of the buffer zone, under the unrecognized, de facto state of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Greek Cypriots live on the southern side, under the Republic of Cyprus, created as a bi-communal republic in 1960. To reach the buffer zone and travel from one side to the other, you need to show your ID or passport at the checkpoint.

I was born in northern Nicosia in 1997 as a Turkish Cypriot, when the checkpoints were still closed and we weren’t able to cross to the other side. I grew up speaking Turkish (more specifically, Turkish Cypriot dialect), learning English from a young age, and choosing French as my optional third language in high school.

I didn’t have the opportunity to choose Greek as a foreign language—the truth is, even calling Greek a ‘foreign’ language is strange when I know my grandparents speak it fluently, having lived alongside Greek Cypriots, Maronites [a Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group], and many other communities.

As for many Cypriots (and Mediterranean people in general), family was a big part of my childhood. We called (and still call) our house ‘the family apartment’—my grandparents lived on the first floor, we were on the second, and my aunt and her family on the third.

But as I look at this familiar street with a different perspective, I feel a certain discomfort: There are just as many streets here that I don’t know as well. Almost a year after my move, I still check Google Maps to find my way around the city.

The checkpoints opened in 2003 when I was just six years old, and it was this same year that the Association for Historical Dialogue and Research (AHDR) was created. Aiming to champion unbiased history education and communication, it opened the Home for Cooperation in 2011 where, a few years later, I did an internship and their café became my office. I helped write the AHDR’s newsletter, translated texts between Turkish and English, and organized events, from talks to languages exchanges to festivals.

Interning at the same time as me was a Greek Cypriot girl and we quickly became friends. We were frequently joined by a clingy stray cat, who we named Karpuz/Karpouzi—‘watermelon’—a common word, as many are, between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Even the cat’s name is a symbol of unity.

I smile as I think of these happy memories. It’s bittersweet, though. When the barbed wire, blue berets and UN cars were blended into my daily work routine, they somehow became my normal. But now, returning after years, I can’t un-see them. And my friend isn’t here this time. Nor is Karpuz/Karpouzi.

In 2015, aged 18, I moved abroad to study and work which I did for nine years until I decided to come back to my hometown. I had an exciting life abroad, mastering English and French by studying and working in the UK, France and Belgium, picking up Spanish during my eight-month adventure in Latin America, and growing my freelance writing career in beautiful Prague. It was Prague where I realized I craved more connection to my roots and a better understanding of my own country.

Eventually, I came back to Nicosia. But this time, I’m living on ‘the other side’—in southern Nicosia, where the majority of residents speak Greek, more specifically, Cypriot Greek. And today, for the first time, I traveled to the Home for Cooperation from the south instead of the north. I felt disoriented, particularly when I saw ‘my’ beautiful Zahra Street behind the buffer zone.

I’m no stranger to feeling disoriented—for one thing, I have a terrible sense of direction. But Zahra Street is one part of the city I do know well. Lined with historical houses that have been transformed into cafés and bars, it overlooks the buffer zone and borders the Venetian Walls of Nicosia that surround the old town.

Looking at this familiar street from a different perspective, I feel a certain discomfort: I realize there are just as many streets here that I don’t know as well. Almost a year since moving, I still check Google Maps to find my way around the city that is my home. Sure, I’d been to southern Nicosia before, as the checkpoints have been open for most of my life, but I didn’t have my go-to spots, favorite bars or cafés. I find myself searching for ‘the best restaurants in Nicosia’ or ‘events in Nicosia now’, as if I’m a visitor. As a travel writer, I think of the advice we often give readers—’Be a tourist in your own town’. And now I am.

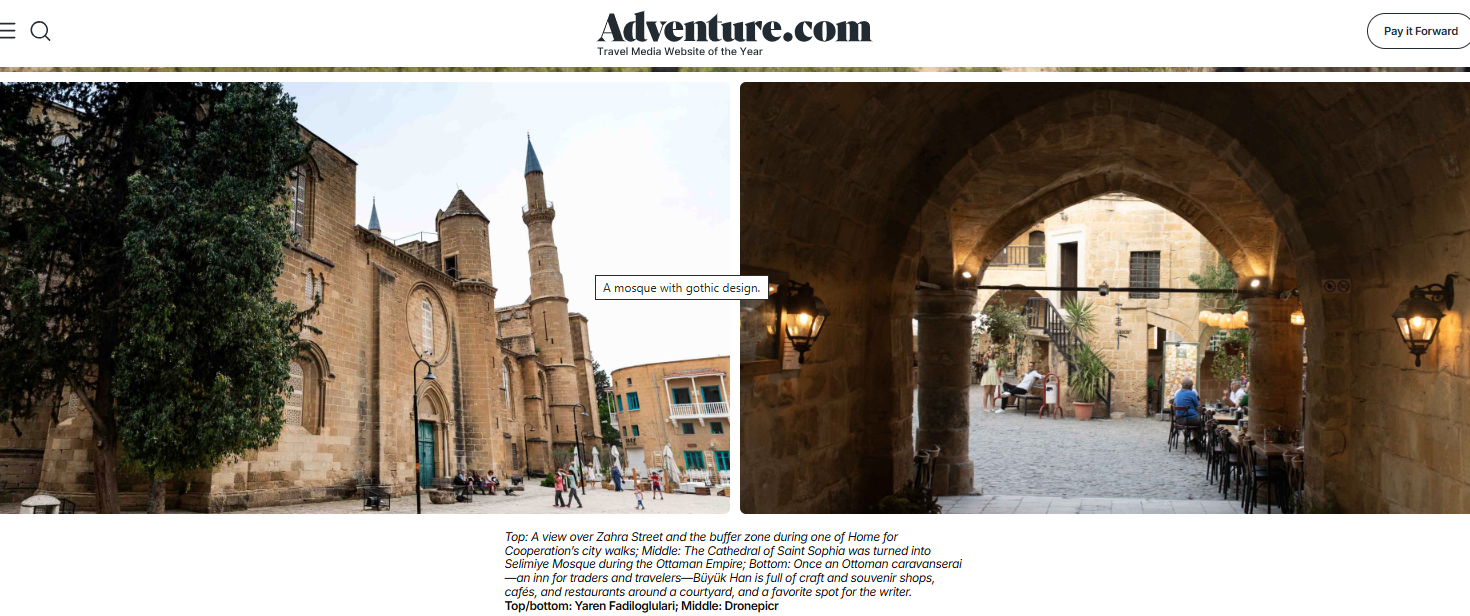

I know I’m not the only one who feels this way. In the book The Traitors Club, Greek Cypriot author Marina Christofides documents her bi-communal friendships and memories. “When the free movement was allowed with the opening of a few checkpoints, I discovered places, like the Büyük Han, I had not known existed, even though they were part of my country,” she writes.

Once an Ottoman caravanserai—an inn for traders and travelers—Büyük Han, falls on the northern side of the divide. It is now a home for craft and souvenir shops, cafés, and restaurants around its courtyard. It’s a place I’ve visited countless times, on school trips or with friends and visitors who always express awe at the inn’s striking arches.

Nicosia and I are finally closing that gap. I learn new things every day—much like how you might get to know a partner once you’ve lived together.

One way you can find your way around Nicosia is through Home for Cooperation’s city walks. Each walk starts at the buffer zone, in front of their center, and experienced guides take visitors across the divide, stopping according to the walk’s themes. A food-themed walk take you to local food spots across Nicosia, and a history-themed stroll uncovers lesser-stories of the city.

“Both locals and international visitors come to our walks,” says Hayriye Rüzgar, a Turkish Cypriot and communications officer at Home for Cooperation. “There aren’t many chances to hear different perspectives and viewpoints about the history and social life of the city,” she tells me. “These walks are exactly about that.”

If cities were relationships, Nicosia would be the long-distance relationship: The one you hold on to, no matter how hard the circumstances. The one you have big dreams and plans with, once you finally close the gap and move in together. Nicosia and I are finally closing that gap. I learn new things every day—much like how you might get to know a partner once you’ve lived together.

Through one of my attempts on discovering places to eat in the city—southern Nicosia to be precise— I learn that the city was named one of the culinary capitals by the World Food Travel Association in 2024. When I picture the number of restaurants in my new area, it makes obvious sense. On the southern side of the divide, I’ve been to many that interpret Cypriot food beyond the taverna. Rous, for example, is a Cypriot fine-dining spot which does excellent seasonal tasting menus with a twist. Their dolma, traditionally rolled vine leaves filled with rice, is instead stuffed with octopus and mussels. Another favorite is Kuzuba, which gets creative with seasonal ingredients and wine pairings; I can still taste the Greek wine and seafood orzo.

A fellow Nicosian, Phivos Phivou, is also closing the gap in his own relationship with Nicosia. He’s a Greek Cypriot friend of my French partner, who lives in the city with me. Knowing I’m Turkish Cypriot, he—quite rightly—assumes my partner knows northern Nicosia well and asks him for suggestions.

“Visit Büyük Han, the largest caravansarai on the island,” my partner tells him. “Walk to Zahra Street and grab a drink along the Venetian Walls. Do check out Selimiye Mosque, which used to be the Cathedral of Saint Sophia. The Ottoman Empire turned it into a mosque. It has Gothic architecture, which you don’t see in a mosque that often.”

I feel I would have given similar tips; and it suddenly strikes me that a French man is giving Nicosia recommendations to a Nicosian from ‘the other side’.

As for me, ‘my’ Nicosia gets broader every single day. I often pass by the Laiki Geitonia neighborhood, now full of craft shops and cafés. The ladies at the Da Vinci Handmade Lace Center, a jewelry shop, know me now and I greet them with a loud ‘kalimera’ (good morning), as I attempt to put my Greek into practice.

My walk might take me to either side of the divide, whether that’s for a coffee near the busy Ledra Street or the good old Zahra Street, offering an unmatched breeze on warm summer evenings. If there’s an interesting exhibition at the Leventis Municipal Museum, I stop by to check it out. A recent one, Sector 2, illustrated how Nicosia became divided at all—I feel a deep pain to think my grandparents lived through that.

I realize pain and discomfort will always haunt me in this city, but I know hope and discovery are there too. I might feel disoriented one day, thinking I’ll never close the gap with my long-distance relationship with Nicosia, but then a smile, a memory, or simply a building, will make me feel right at home. Because, after all, it is home.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.